Where Have All the Orphanages Gone? Lynchburg Orphan Asylums

By Cathy Dalton, Museum Experience Leader

Popular stories from the past such as Charles Dicken’s Oliver Twist and the familiar 1977 Broadway musical Annie, based on the 1924 comic strip Little Orphan Annie by Harold Gray, remind us that orphanages were found often in history, and not in a very positive light. Orphanages were essential immediately after epidemics such as cholera 1832, diphtheria 1906, typhoid in 1907, measles in 1912, or influenza 1918.

Lucy Mina Otey. Courtesy: Find a Grave Memorial no. 10525013, Maintained by S.G. Thompson (contributor 46616521).

Anne Norvell Orphan Asylum

Present-day view of the original Anne Norvell Orphan Asylum

Courtesy of Cathy Dalton

The first known orphanage in Lynchburg was founded by Lucy Wilhelmina Norvell Otey (1801 - 1866). The Anne Norvell Orphan Asylum of Lynchburg, named after Otey’s mother, was officially recognized by the state government Feb 16, 1846. It stood at 112 Federal Street for approximately two decades, but it did not survive her passing. The building still stands in its original place as a private residence.

Miller Home, originally the Lynchburg Female Orphan Asylum

Female Orphan Asylum booklet

Gift of the Junior League of Lynchburg, X-778

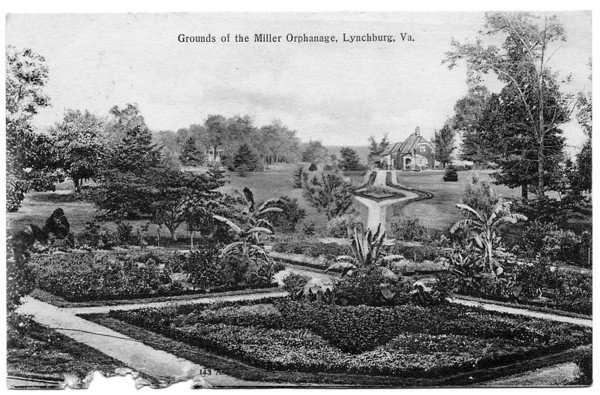

In 1875, the estate of wealthy Samuel Miller (1792-1869) provided for the Lynchburg Female Orphan Asylum a trust of $151,500 and forty-six acres of land for a building site. He made his money in wise investments in tobacco, railroads, and as a merchant. Since 1875, the Miller Home has cared for more than 1000 girls. The first four story building housed 100 girls at a time. The Miller Orphanage, now known as the Miller Home for Girls, opened in 1875 in the area where the Plaza stands today on Memorial Avenue. Although the home has moved, the Miller Home remains operational today. On display in this postcard image are some of the Orphanage's well-maintained gardens and the old gate house in the background. It had extensive, planted fields, green houses and gardens. In 1946, The Lynchburg Female Orphan Asylum sold large tracts of land to the City of Lynchburg to defray costs. E. C. Glass opened on 50 of the acres in 1953. The E.C. Glass High School was completed in 1953 and is located on Memorial Avenue at Langhorne Road. This undated photo depicts the main entrance of the school. The Lynchburg Female Orphan Asylum was renamed the Miller Home. They moved to a new facility on Westerly Drive in 1959.

“Miller Home serves a diverse population and believes that the differences each girl brings is what makes the Miller Home a special place to call home.”

Colored Orphan Asylum and Industrial School / Southern Negro Orphan Asylum

The Civil War disrupted family life due to casualties and Emancipation. In the South, the social and economic structures changed drastically during Reconstruction. The Virginia General Assembly chartered the Southern Negro Orphan Asylum in 1890, as a private institution, supported by charitable donations. It was renamed in 1892 as the Colored Orphan Asylum and Industrial School. Its general manager was the Jewish convert to Episcopalianism, Reverend Abraham Jaeger. During the years 1890 to 1892 the corporation built a school, with housing for staff, on land three miles outside of Lynchburg. The school supported from 60 to 100 children between 1892 and 1898 in the name of “racial uplift.” Jaeger ran the orphanage in line with the white Progressive idea of the time that emphasized individual responsibility over systematic oppression. In 1898 Abraham Jaeger purchased the property and school, rather than allowing it to fall into bankruptcy. By 1900 the census counted just 16 children at the site. The Reverend Jaeger was not successful in raising funds because of his tractable nature which found him at odds with both the church and the law. According to a Richmond newspaper, Jaeger reportedly attacked a bishop and was subsequently excommunicated from the Episcopal church.

“Jaeger, and the Southern Democrats he was appealing to, were reacting against the freedoms black people had gained during Reconstruction and striving to restore the former racial status quo by raising black children to be docile and subordinate.”

This contract grants Jaeger guardianship of orphans Edmonia Smith, Delia Moore, Clara Robertson, and Louisa Robertson. 1896, courtesy of Ancestry/

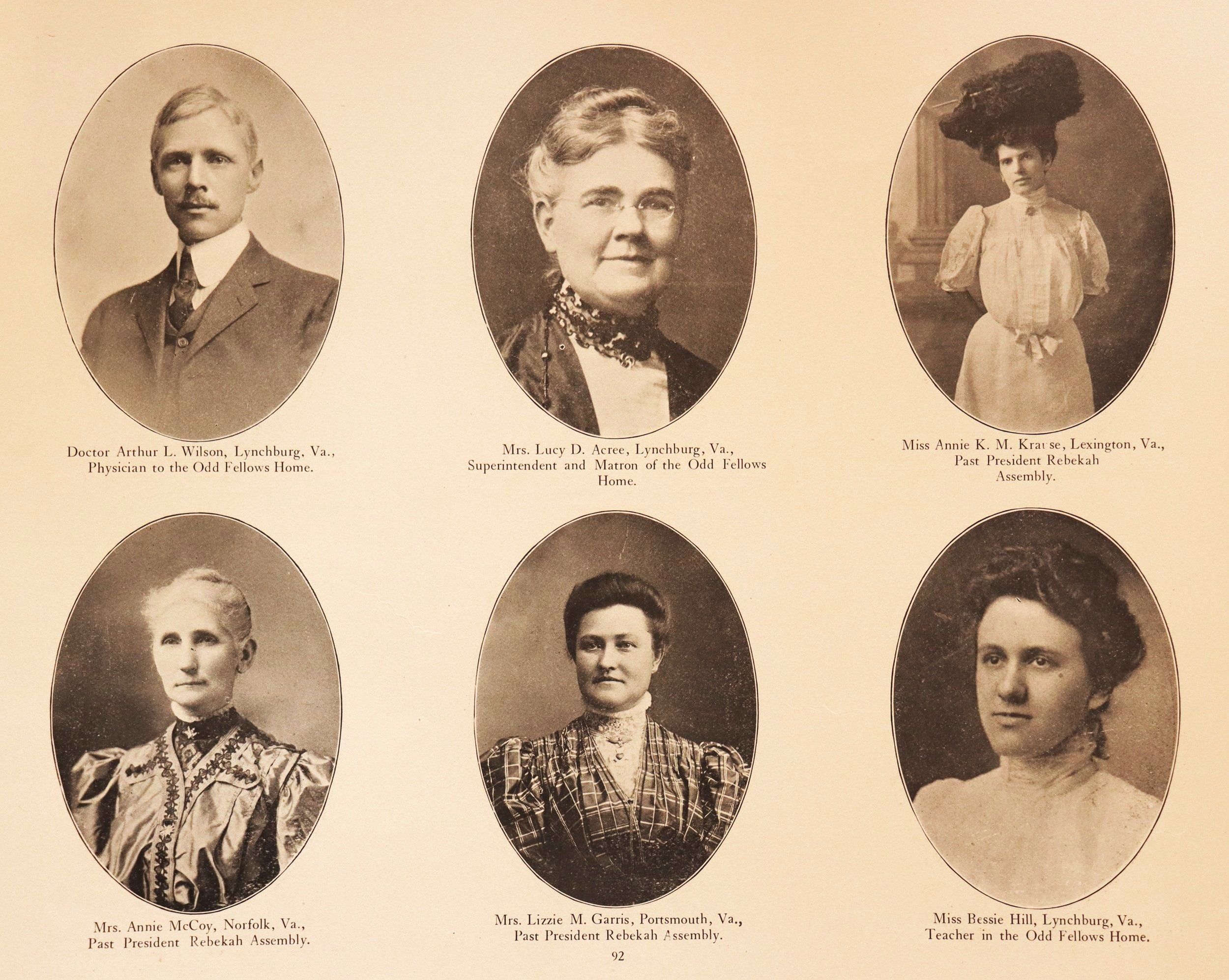

Odd Fellows Home

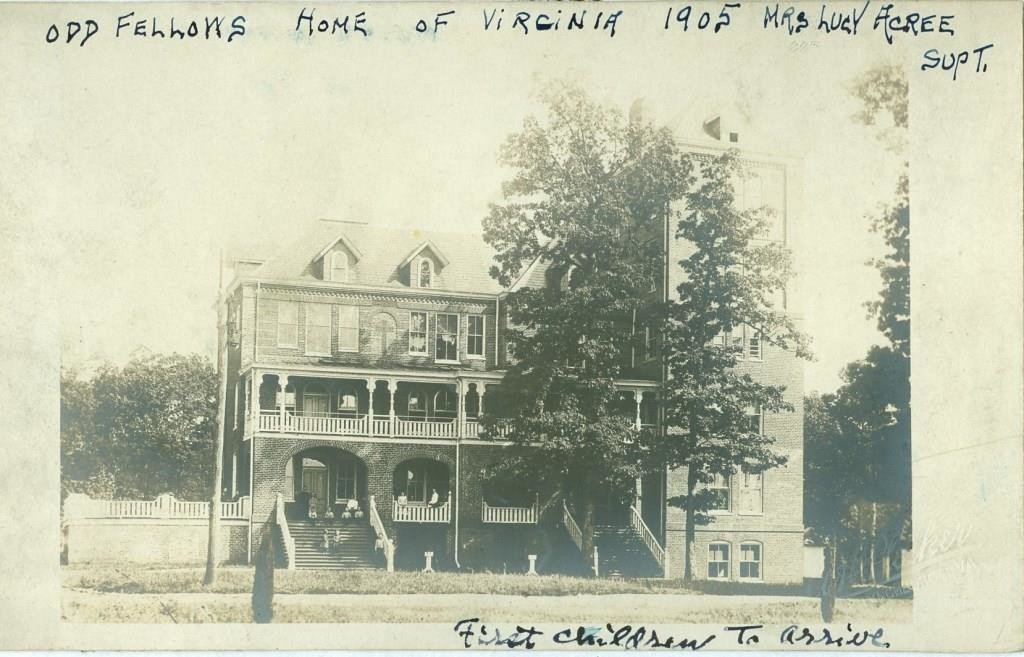

Several organizations looked at purchasing the property to open a white orphanage, but some were concerned about housing white children in an orphanage that had formerly housed children of color. One of the orphanages was the Presbyterian Home. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows purchased the property in 1902. Mentioned in the Annual Report of Trustees and Superintendent Odd Fellows Home, 1906, A. Jaeger had made a lease with a brick manufacturer to remove clay from one of the fields, expiring in 1912. The conflict was settled out of court for $500 with additional lawyer’s fees. Even after leaving Lynchburg for Chicago in 1902, Jaeger’s mismanagement of funds remained. Also, in the Annual report is a listing of thirty-nine white children by name and origins. It states that the children are healthy, as the physician prevented a diphtheria outbreak, and the students receive regular lessons nine months of the year. Architects Frye & Chesterman were consulted to design accommodations for aged Odd Fellows and widows on the Odd Fellows Home campus. The August 1920 The Virginia Odd Fellow newsletter states there were 114 residents with 10-12 approved applicants waiting for arrangements for admission. By 1963, the Orphan’s home had closed and 88 acres at the end of Elmwood Avenue were purchased by The Odd Fellows Home of Virginia, Inc. where they opened a retirement home. It closed in 2015 after 113-year presence in Lynchburg.

Evening News, Volume 20, Number 98, 27 October 1909, Roanoke, Virginia, Page 3, Column 2.

Presbyterian (Orphan’s) Home

At the same time as the Odd Fellows Home came into being, the Progressive Movement realized that institutionalizing orphans was not the best way to raise children. The cottage system for orphanages was developed to support children in a more family style environment. Children were organized into small family units with a “cottage mother” in each building in order to expose them to a more supportive family dynamic. The Presbyterian Home was in development at the same time as the Odd Fellows Home. Both groups looked at the Jaeger property. The Presbyterian Synod of Virginia also looked at the Westover Hotel and the Ivey Farm. The Presbyterians purchased the Ivey 317-acre tract in 1903 to open the Presbyterian Orphans Home. The Ivey Farmhouse, along with two cottages, were used as the orphanage until 1910. In 1909 a fire broke out in the three story Shelton cottage. Leading to the death of five of the 24 girls. The story gained national attention.

“…[the cottage] system was thought to transform young boys and girls into individuals who were far more likely to become productive members of society than those who were churned out of the larger “institutional style” orphanages that packed children into dormitories in mammoth buildings.”

At that time the Presbyterian Home provided the rare characteristic of having a bed for each child. Construction began in 1909 for the horseshoe shaped campus. When completed, it consisted of six residence halls, a superintendent’s house, an executive building (all constructed of brick in the Georgian Revival style) and a Greek Revival gymnasium. By 1920, 116 children were in residence. In 1922, The Presbyterian Orphanage High School opened. The football team was the subject of a Universal Studios Newsreel, called “The Shoeless Wonders Win Gridiron title in Barefoot Play.” The team was undefeated and unscored upon for eight years.

The 1930 United States Census indicates that 122 children were living on site in five household units. In 1944, two boys drowned while swimming in the James River. Subsequently, a pool was built inside the horseshoe. In 1982, the licensed capacity of the home was reduced. There were 69 residents. In 2014 the last child resident left the Presbyterian Home, and the new brand HumanKind was released. Over 10,000 children had been nurtured at the campus. While no longer an orphanage, HumanKind serves the Lynchburg community through financial education programs, mental health counseling, early childhood resources and services for adults with disabilities.

“...we believe strong individuals and families build stronger communities.”

Presbyterian Home Campus, now HumanKind. Lynchburg Museum Collection.

Traditional orphanages in the United States began closing following World War II, as public social services were on the rise. By the 1950s, more children lived in foster homes than in orphanages in the United States, and by the 1960s, foster care had become a government-funded program. Foster care is the choice for supporting children in need of attention while awaiting adoption or returning to their biological families. American orphanages no longer exist.