Public Executions in Lynchburg, Part 3

By Christian Crouch, Assistant Curator and Museum Technologist

View of the James River below Lynchburg in the mid 1800s, Edward King, Donated to the Lynchburg Museum System by Fidelity National Bank

[Content Warning: Graphic Description of a Hanging]

The day has finally arrived, the one you have all been waiting for...the day we release the final installment of our trio of execution stories!

For those of you that may have thought that I was referencing Halloween - shame on you. I know that all of you are far more excited and interested about the final chapter of these stories rather than some measly nationally recognized and celebrated holiday enjoyed by millions.

This chapter takes us way back. All the way back to the elder days of May 22nd, 1829. Some of you may remember a certain other blog post (written by yours truly) that dealt with a servant girl being tortured by a family from New York in Lynchburg. If you haven’t read it, take a jump over there by clicking right here[1] . Otherwise, keep in mind this was in the exact same year as that whole debacle. The year 1829 brought with it the swearing in of Andrew Jackson[2] [3] as president of the United States (and most likely a certain amount of swearing from Jackson himself), the first typewriter patented by William Austin Burt, and the first gold rush in Hall County, Georgia.

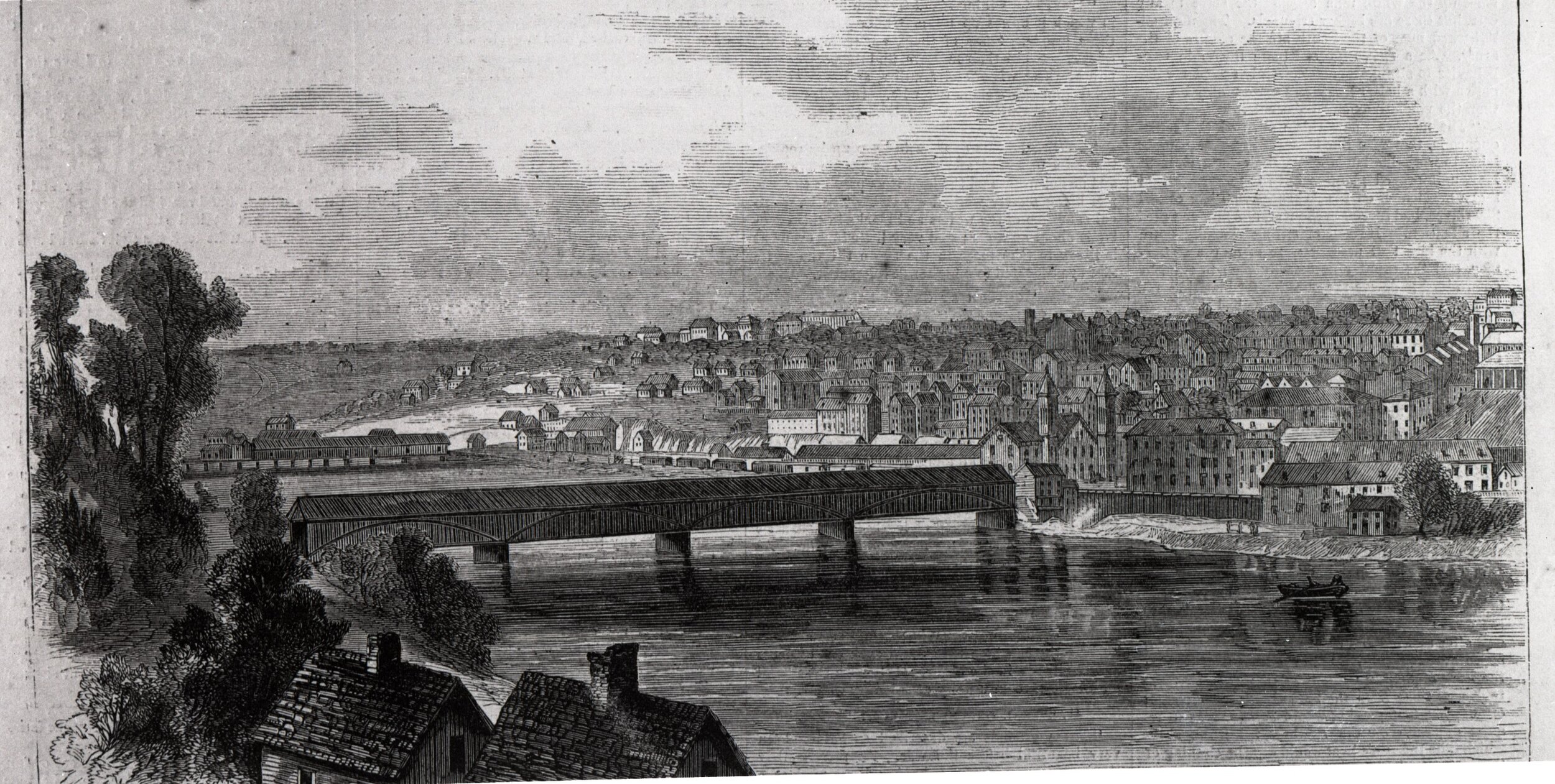

Lynchburg from across the James River in Amherst County, Harper’s Weekly, June 2, 1866, Artist: Theodore R. Davis, gift of M/Mrs. Carl McCartney

We don’t know much about John M. Jones before his incident with George Hamilton. One source says that he was an slaveholder, and another mentions his extended family either owned or operated a bawdy-house down near the James River; but not much is known about the man himself. John M. Jones comes on to the scene rather suddenly with reports from citizens around 3:00pm of a fight near the riverfront, most likely inside a tavern or brothel where the two men were reportedly liberally partaking of “blue ruin”[1] (otherwise known as gin). The fight began after a local sex worker levied some “provoking expressions”[2] towards Hamilton, who in response, struck the woman. It’s unclear whether Jones was a regular customer of the woman, just knew her in passing, or whether he acted as protector in the interest of his uncle who owned a nearby brothel; but, regardless, he took offense to Hamilton striking the woman and came to her aid. Many believed the manner was settled after this fight saying “[witnesses] seem to have left the house under the impression that Jones and Hamilton had settled their dispute in an amicable manner, and had parted with no desire or intention to renew it.”[3]

Hamilton is said to have returned to his boat that he had moored a short ways away on the riverfront of the James River and Jones took refuge in the aforementioned brothel that his uncle owned - a man with the last name of “Black”. While in the brothel, Jones found himself a dirk (a small pointed dagger primarily used as a piercing weapon) and began telling others of his plans to go down to Hamilton’s boat and give him a piece of his mind. While this was happening, Hamilton was strolling up to the Black house, unarmed, and was warned by a mutual friend that Jones was in the building armed and still angry. Not wanting to be caught on the bad side of another argument, this time with a weapon involved, Hamilton returned to his boat and found himself a “large stick.”[4] The description of the stick is as such, simply a large stick, but could easily have been some kind of wooden implement like an oar or pole.

Genius of Liberty, Volume 13, Number 22, 6 June 1829

As Hamilton again approaches the Black house, Jones is heard by a few inside the building proclaiming “God damn him, I will see his heart’s blood before night!”[5] Meeting once again, this time outside of the Black house, the two argued and Hamilton struck the first blow against Jones with his large stick “over the shoulders of another man.”[6] This attack could have easily killed Jones “if the assailant had been in a position to secure a fair blow.”[7] Receiving not much more than a head wound, Jones retreated within the house once again, while Hamilton proceeded to throw rocks against the windows of the establishment trying to stir up more trouble. In the trial, the defense conceded that Hamilton did in fact strike the first blow in the altercation, but if that blow had actually killed Jones then he would have been convicted of the same murder charge anyway - invalidating any defensive claim.

Jones, heated and potentially still a little inebriated, visited a local gunsmith about “600 yards distant from...the first combat” and purchased a weapon. Around 30 minutes after purchase, he made for Hamilton’s boat and boarded it. Hamilton was said to be “on the rim of the boat” with “two or three of his comrades”, one of whom had a burn scar on his face - supposedly, and ironically, from the faulty discharge of a weapon. One of the three men “begged him not to fire”[8] but Jones’ mind was already made up. Advancing towards Hamilton, Jones pointed his weapon at the man and fired - knocking him backwards into the water. Upon hitting the water, Hamilton is said to have stated “Boys, I am gone!” Jones then unsheathed his dirk and pulled Hamilton out of the water “intending to complete the murder”, but Hamilton was already dead.

Jones was taken into custody and his trial commenced on Wednesday, August 19th, 1829 and he was pronounced guilty on August 22nd. A few well-known local names pop up in the trial of Jones as well. His defense included James Garland, Chiswell Dabney, and Major J. B. Risque while the prosecution was singly handled by Sterling Claiborne with Christopher Anthony “conclud[ing] for the commonwealth.”[9] The case was also appealed no less than three times; the first on “the allegation that the verdict of the Jury is not warranted by the evidence”[10], the second that “the presiding Judge should have permitted a re-examination of the [40] witnesses”[11], and third that “three of the Jurors had expressed opinions adverse to the prisoner, previous to being impaneled.”[12] Other than a single stay of execution on July 15th, 1830[13], none of these appeals were strong enough to warrant a re-trial. Jones was slated to be executed on August 16th, 1830.

The time finally rolls around and the day is set to be a spectacle. Crowds of people flooded the Methodist Graveyard (Old City Cemetery) and the numbers were estimated to be between eight and fifteen thousand people - all to witness the execution of John Jones. In fact, again referencing the Ann Hendershot story, the woman who came to evaluate Ann and her similarity to her lost daughter Susan Allen came to Lynchburg just the day before and could have easily been at this event. At noon on the appointed day, the jail was opened, Jones was led into a wagon, and seated upon a “plain pine coffin.”[14] The wagon was driven down Clay Street, up Fifth and finally “down the hill near old Tate’s Mill.”[15] The journey was accompanied by the Artillery and Rifle militiamen, the presiding reverend, and some of the crowd. Upon reaching the gallows, the proceedings;

Plaque at Old City Cemetery. Photograph courtesy of Tanya Anderson

…opened with singing; then Rev. E. L. Russell, of the Second Presbyterian church, led in prayer; Rev. Charles Calloway, of the Methodist Episcopal church, preached an appropriate sermon, and was followed by Rev. William Holcombe, of the Associated Methodist church, who made a feeling address.

All of this went on for three hours.

At around 3 o’clock Jones was led up the stairs of the gallows. He gave a short speech and he had a bag slipped over his head. Upon dropping the man through the gallows however, the rope around his neck snapped and he fell to the ground below. He cursed, was given a small glass of water, and was summarily re-hung on the gallows with his body on view for over an hour. His body was then taken from the platform and brought into the above mentioned mill where “some say an autopsy was performed”[16] - why an autopsy was needed, we can only guess.

It was said by some of the African American men “who lived near there”[17] that every night after the execution a ghostly white light would appear in the mill and rattle the windows violently. After shaking the windows, “something appearing in white came to the window and threw a man’s skin into the pond.”[18]

So there we go, the stories of three men who were publicly executed in Lynchburg, Virginia and concluding with a small ghost story. If you read all this way and through all three stories - thank you for going down this rabbit hole with me and doing a little bit of learning in the process. I encourage you to look up some of the sources that I pulled these stories from, nearly all of them are accessible online in full or in part and contain some details that I had to omit in order to make the stories as short as I felt I could make them. Lastly, be on the lookout for the final chapter of this story sometime later in the form of Joe Higgenbotham in 1902 - the last execution in Lynchburg.

Happy Halloween!

——————————————————-

[1] Phenix Gazette, Volume 5, Number 1246, 4 August 1829.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Phenix Gazette, Volume 5, Number 1246, 4 August 1829.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Phenix Gazette, Volume 5, Number 1191, 30 May 1829.

[9] Lynchburg and It’s People by William Asbury Christian, p. 107.

[10] Phenix Gazette, Volume 5, Number 1246, 4 August 1829.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Constitutional Whig, Volume 7, Number 50, 16 July 1830.

[14] Christian p. 107.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Christian p. 108.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.