Exhibit Curated and Digitized by Melissa Vandiver

Medicine in Lynchburg

Before the Civil War, there were no ‘hospitals’ as we think of them today. The term had negative connotations for the upper classes, as they were generally considered as a kind of hospice for victims of war, poverty, and mental illness. As a standard, doctors made house calls to those who could afford it, and people took care of their ill in the home.

After the success of Lynchburg’s hospitals in the Civil War, and the increase in medical training, the idea of medicine outside the home became more popular. On April 5, 1886, local Masons established the Marshall Lodge Home & Retreat at a rented building at Washington and Church Streets; though their success was slow, eventually they purchased a larger property. The care home later became a public non-profit, and the building had to be enlarged three more times. Only wealthy families could afford to send their ill to this resort-type hospital. As this and other care homes grew, in 1893 around 17 of the 20 doctors in Lynchburg formed the Lynchburg Academy of Medicine to encourage collaboration and the easy spread of new practices.

Marshall Lodge Memorial Hospital, colored postcard

Courtesy of the Lynchburg Museum, 74.357.1

In contrast to the comforts of the Marshall Lodge, a dilapidated alms house on Hollins Mill Road served as hospital and clinic for Black citizens and the poor in Lynchburg up until 1912 when the Lynchburg Hospital was opened. Director of the City Health Department and overseer of the Lynchburg Hospital was Dr. Mosby G. Perrow, who stated in 1925: “[in the hospital’s mission] preference is given to charity cases, except for colored, there being no other hospital in the city for colored patients.” Over time the hospital attracted paying customers and demand increased until 1956 when Lynchburg General Hospital opened on Tate Springs farmland. In 1924, the Virginia Baptist Hospital (VBH) opened on Rivermont Avenue in a building designed by local architect Stanhope Johnson. At the time, it was described as “one of the most modern, up-to-date hospitals in the South, free from noise, dust, and smoke.” Like Perrow, VBH board chairman O. B. Barker wanted to be as magnanimous as possible, and envisioned the hospital as “undenominational in its service and patronage, and every patient, regardless of sect or religious belief, [would] be given every kindness and consideration.”

Also notable is the “Lynchburg Life Saving and First Aid Crew,” formed after the devastating fires in 1933-4 at the Lynchburg Transient Bureau on 12th Street and the McGehee Furniture Company on the corner of Main and 10th Streets. Their purpose was “to assist fellow citizens and countrymen in emergencies and life threatening situations,” and founders were mirroring the first rescue squad in America, formed six years earlier in nearby Roanoke.

Poison in Medicine Today

With the advances of modern medicine, many toxic materials are being tapped for compounds that are effective, non-toxic treatments for certain ailments. Thousands of toxins have been and are being studied for their potential uses in new drugs. For example, the yew tree is deadly to humans - however, a chemical isolated from the bark was found to be useful against the progress of some cancers. From that toxic chemical, a lab-created compound called paclitaxel was made and has been available commercially since the late 1990s and has been found to be effective in treating breast, lung, and other cancers, in preventing the re-narrowing of coronary arteries in stent recipients, and in treating AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. Other notable toxic plants with medicinal uses include the opium poppy, which is used for pain relief; foxglove, which is used to treat irregular heartbeats; and sweet wormwood, which fuels a widely used malaria treatment. Scientists are also looking at poisonous and venomous fungi and animal species for potentially life-saving new drugs. For example, spider and scorpion venom may help with things like pain and heart disease, and cone snails produce compounds useful in pain medication, and could potentially be used in the future to fight epilepsy, Alzheimers, and Parkinsons.

Right: An undated black and white photograph of five unidentified men in white hospital uniforms standing in front of the old Lynchburg General Hospital on Federal Street and Hollins Mill Road

Lynchburg Museum System collection, 2017.21.7

Patent Medicine - The Unregulated Drug Market

Arsenic, Mercury, Cyanide were all commonplace in the 19th century medicines, and all now known as highly toxic. As there was no governmental regulation, the patent-medicine trade boomed, with unqualified medicine makers created tonics, pills, pointments, liniments, and dry-herb mixtures claiming to cure all ailments - things we know today as ‘snake oils’ for their dishonestly. Tonics in particular were successful, with sensational marketing and the idea of ‘seasonal conditioning,’ to help one’s constitution adjust to a change in the weather. Especially in the South, tonics were consumed daily by men, women, and children. Any successful tonic had a catchy name, eased pain immediately, gave ‘a cheerful warming glow to the whole body,’ tasted strongly of herbs, and acted as a laxative. Distributors sold to general stores at a set price and then allowed the stores to sell at a price the owner thought the community would pay.

The use of narcotics was also incredibly common, to the point that rural ‘quack’ doctors often used them on themselves. Because medical training was scarce, doctors prescribed morphine, laudanum, and opium to calm patients with any ailment the doctors couldn’t diagnose. Many doctors and patients were able to buy and abuse narcotics quite easily.

Turpentine and pine tar were considered the most important of all medicines in the 19th century, and could be found in every home. It was given (with a spoonful of sugar!) to children with colds, people with cut fingers, backaches, kidney troubles, sore throats, rheumatism, croup, pneumonia, toothaches and earaches. Although an antiseptic, turpentine certainly did more harm than good.

In the late 19th century, after accepting the toxicity and negative side effects of certain drugs, some advertisers were quick to change their tune, such as in this ad for Bromo Seltzer, an antacid, described as a cure-all containing “no antipyrine, no cocaine, no morphine, absolutely nothing deleterious” in 1895. Despite this turn, it wasn’t until 1906 that the US government passed the first Pure Food and Drug Act which began the regulation of drug creation and distribution.

Left: Page from the "Woman's Edition of the Washington Times,” advertisement for Bromo Seltzer, used by Lumsden & Hamner, Druggists in Lynchburg, 1895

Gift of Miss Charlie H. Lumsden, 83.1.35

Common Poisons as Medicine

Acriflavine- Produced here by Wheeler’s Pharmacy in Lynchburg and similar to Mercurochrome, is used as a dye and antiseptic.The label indicates the following ingredients: Neutral / Iothion / Butyn Sulfate / Elsterium / Mercury Cyanide. Mercury cyanide is both toxic and highly combustible, and can be deadly. Although mercury is a strong antiseptic, similar products today do not contain either dangerous compound.

Acriflavine

Produced here by Wheeler’s Pharmacy in Lynchburg and similar to Mercurochrome, Acriflavine is used as a dye and antiseptic. The label indicates the following ingredients: Neutral / Iothion / Butyn Sulfate / Elsterium / Mercury Cyanide. Mercury cyanide is both toxic and highly combustible, and can be deadly. Although mercury is a strong antiseptic, similar products today do not contain either dangerous compound.

Gift of Mark C. Johnson, 2008.50.3

Medical Turpentine- Venice Turpentine, made by Magnus, Mabee, and Reynard of NY, and distributed by Strother Drug Co. in Lynchburg. A very flammable liquid, turpentine is used for lamp oil, solvent, paint thinner, and water repellant - as such, it is very toxic when ingested, causing issues from harsh side effects to destruction of the kidneys and bleeding in the lungs. However, turpentine, made from distilled pine resin, was used as medicine for thousands of years as an antiseptic, to stop heavy bleeding, and in the Romans’ case, to treat depression. Turpentine mixed with sugar is still considered a folk remedy in some places today, and interestingly, one side effect is one’s urine smelling like violets. One doctor in 1821 prescribed a drink of turpentine every few hours to kill tapeworms. Kentucky Historian Thomas D. Clark wrote:

“King of the [medicines] was turpentine, a product of the tidewater pine forests. Turpentine had three important medical requisites: It smelled loud, tasted bad, and burned like the woods on fire.”

Turpentine was widely used and produced in the southern United States, particularly early on when the British tapped pine forests for sealants for their wooden ships. Whole forests were utilized, creating a kind of ‘turpentine belt’ where enslaved people were forced to do the painstaking task of creating and distilling the pine resin. Resin was collected through a destructive process called boxing, where people would cut a deep pocket into the bottom of the tree, causing it to send resin to the hole to seal it. Some of the resin would flow through the wound, and it would be collected in boxes at the base of the tree.

Venice Turpentine

Jar bearing label identifying contents as "Venice Turpentine - M.M.&r R." manufactured by Magnus, Mabee, & Reynard of New York, and secondary label indicating product distribution by Strother Drug Company in Lynchburg.

Gift of Mark C. Johnson, 2008.50.5

Arsenic- The Industrial Revolution required the increased smelting and burning of mineral ores and coal which produced arsenic trioxide, known as white arsenic or simply arsenic. As a very cheap waste product, arsenic was used in a wide variety of products, including but not limited to medicines, candles, stuffed animals, hat ornaments, embalming, clothing dyes, insecticides, painted toys, wrapping paper, beer, wine, wall paper, and candy and confections. One of the most famous uses was in Scheele’s Green, also known as Paris Green: an incredibly vibrant emerald green pigment used in cloth, paper, and candy, although many pigments were made with arsenic dating back to ancient times. People would be slowly poisoned over time when surrounded by arsenic-containing objects. It is thought that such poisoning contributed to Napoleon’s death, as his autopsy showed stomach cancer and his hair samples showed high levels of arsenic.

In the 19th century, as it was very commonly used as vermin poison, anyone could go pick up some arsenic at the store and as its side effects were mainly gastrointestinal and therefore non suspect, it was often used in deliberate poisonings. The side effects were typically a slow, gradual decline in health that would go unnoticed. Until a woman was sentenced to death in 1873 for poisoning three husbands, a fiance, her mother, and several of her 15 children for insurance payouts, there was no legal recognition of the toxicity of arsenic, and even then it took another decade for medical consensus that arsenic was toxic at any dose.

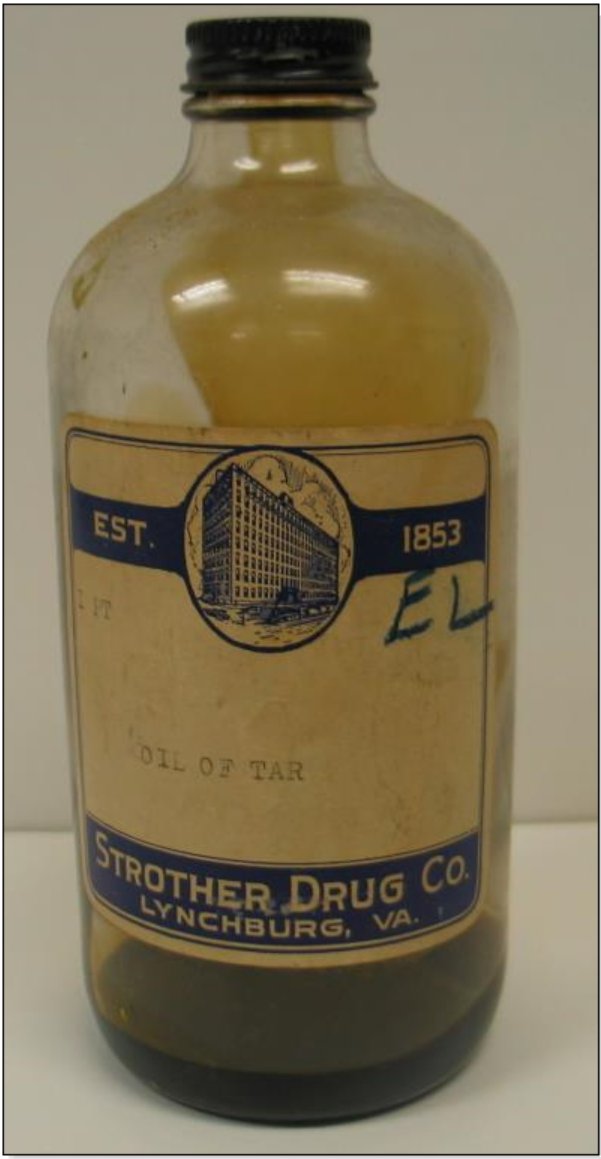

Oil of Tar

Made and distributed by Strother Drug Co., Oil of Tar is made with coal tar, a byproduct of the coal processing industry, used in both medical and industrial ways. Medically, Oil of Tar was used as early as the 1800s as a topical cream to treat psoriasis and dandruff. It worked as an antifungal, anti-inflammatory, anti-itch, and anti-parasitic medication. It was also widely used to preserve roads, railroad ties, and as a dye; Coal tar was listed as a carcinogen (cancer-causing) in the first government report on carcinogens in 1980.

Gift of Mark C. Johnson, 2008.50.4

Mercury- Most famously used in medicine to treat syphilis from the 1500s til the 1910s when another treatment was formulated, Salvarsan and NeoSalvarsan; unfortunately, these treatments used arsenic instead. Finally, as science became more sophisticated, syphilis became curable in the 1940s with the development of penicillin. Mercury today is considered one of the most dangerous elemental toxins and a harmful environmental pollutant, but the iconic metallic liquid was in use in ancient Greece, India, Persia, China, and the Middle East. Mercury products were some of the most commonly used drugs in Asian, European, and later American medicine.

Because it was considered to be a cure-all, mercury was used to treat a wide variety of ailments including but not limited to: inflammation of the nose and throat; corneal stains; ulcers and warts; as a laxative; to stimulate biliary function; against diarrhea and vomiting; against dropsy; against spleen, liver, and lung diseases; and as recently as the 1990s, as a spermicide in chemical contraceptives and in antiseptics. Doctors have managed to separate certain compounds to be non-toxic, and these are still used in things like dental amalgams, saline solutions and eye drops, vaccines, and cosmetics.

Dr. Moffett's Teethina Powders

Box containing “Dr. Moffett’s Teethina Powders”, manufactured by the C. J. Moffett Medicine Co., Columbus, Ga. Used to ease the pain of teething babies - each packet advertised as containing one-eighteenth gran of calomel, a mercury derivative, with busmuth subnitrate, sodium citrate, cassia and calcium carbonate.

Gift of Mark C. Johnson, 2008.50.8a

Pandemics and Epidemics in Lynchburg History

As the ability to travel increased and populations became more dense, diseases quickly spread throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Poor sanitation, inadequate health practices, lack of plumbing, stagnant water that brought flies and mosquitoes, and the lack of quality testing of water and milk all contributed to perfect conditions for rampant spread of diseases.

1830s — Cholera reached Richmond and Norfolk, which prompted Lynchburg city officials to organize its first Board of Health, which prevented an outbreak by cleaning the densely populated town and banning the sale of fruits that carried the disease.

1832 — Scarlet fever killed many, children in particular.

1855 — Yellow Fever outbreaks were reported on the coast in Virginia, and despite welcoming trains of refugees from affected areas, Lynchburg citizens were spared the disease.

1860s — Poor sanitation among Civil War soldiers grouped by the hundreds created a haven for diseases, including dysentery and diarrhea, measles, and smallpox, which was the most feared as it was quick-spreading and deadly. Although we know that the smallpox vaccine had been effective long before the Civil War, a less sophisticated version of which George Washington famously used on his troops in the 1770s, neither the North nor South were given the vaccine. Soldiers struck with smallpox in Lynchburg were sent to Dr. John Jay Terrell’s Pest House in the city cemetery. Nearly 500 soldiers died in Lynchburg, only around 100 of which could afford burials, the rest being buried collectively in a pit. Dr. Terrell and associate Dr. John R. Page conducted a landmark pathological study on a similar disease in horses, and found no cure but only prevention, recommending uncrowded, well-ventilated stables as well as good sanitation, healthy diet, and destruction of infected animals.

1918 — The influenza pandemic died out by 1919 due people either dying or developing immunities. However, the disease had a 10-20% fatality rate, killing around 675,000 US citizens, and 500 million people worldwide, or 1/3rd of the world population. Immediately following World War I, which killed about 9 million people, the disease was spread initially by the density and movement of troops. It was first reported on a military base in Kansas and was worldwide within weeks. While records in Lynchburg are scarce, we do know that a Petersburg Funeral Home was asked to help with the dead. The first mention in the Lynchburg News was on October 3, 1918, which noted the daily spread of the disease, and the next day reported four deaths - a freshman at Randolph Macon Woman’s College, a 10 year old girl, and two adults. By October 15, state officials estimated 200,000 cases, but lack of recordkeeping suggests many more. Quarantines were imposed, schools were shut down, and businesses operated on greatly reduced schedules; organizational meetings and social events were canceled on a wholesale basis.

1957-58 — Another influenza pandemic killed about 70,000 US citizens and about 2 million worldwide.

1968 — Influenza killed about 34,000 US citizens and about 700,000 worldwide.

1981 — To date, HIV/AIDS has killed 35 million people worldwide.

2002-3 — SARS Coronavirus (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) infected 8,098 people worldwide, killing 774 people. Only 8 people in the US were confirmed to have contracted it.

2009-10 — The CDC estimates 150,000 to 575,000 people died in another influenza epidemic. In Virginia, a total of 37 deaths occurred. Like the 1918, this affected young people whereas the yearly seasonal flu tends to affect the elderly.

2019-present — To date, the total deaths from SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) in the United States comes to around 826,000 and global deaths stand around 545,000,000. In Virginia 15,643 deaths have occurred, and 216 in Lynchburg all as of the first week of January 2022.

1815 Medicine Chest

Medicine chest ca. 1815, from Washington D.C; pine and poplar stainted and shellaced to mimic mahogany; prepared by Dr. James Ewell.

Lynchburg Museum System collection, P-2003.1.1